A temporary memorial has been set up in Palmeira Square where every evening at 6.30pm, people meet to light candles and lay stones. They pray for the dead and the living, remembering victims of the Hamas attack on 7th October.

I visited the Square before Hanukkah, joining a small group gathered around twenty or thirty flickering candles, laid among stones, alongside names of the captured and the dead.

I lit a candle and listened as a man said Kaddish for the dead. I didn’t understand the words, but could say Amen. I realised that not since I was a child had I prayed for the Jewish people. I didn’t think I still needed to.

I grew up among racists in Apartheid South Africa. Casual anti-semitism was common, especially amongst white men. In the decades following the Eichmann trial, newspapers were full of images of the splay-limbed, emaciated dead and dying, forced into crematoria or bull-dozed into vast mass graves. I was haunted by them.

I remember my shock, when I learned our kindly family doctor, had railed against Jewish doctors in Durban, telling my grandfather “Hitler had the right idea”. He was a UK immigrant, educated not in South Africa, but here in the UK. British people can rightly be proud of their country’s heroic struggle against nazism. But this shouldn’t blind us to the fact that, then as now, a significant minority were anti-semites.

I fear the growth of anti-semitism in Britain. Individual Jewish people are not responsible for the actions of the Israeli government, yet they are being condemned as if they are. Communities that have been here for generations, refugees from pogroms and the Holocaust, are being treated as hostile aliens by well-funded secular ideologues and anti-democratic religious zealots. Old prejudices linking Jewishness to corruption, wealth and the exercise of clandestine power are re-surfacing and we need to ask why.

I fear the growth of anti-semitism in Britain. Individual Jewish people are not responsible for the actions of the Israeli government, yet they are being condemned as if they are. Communities that have been here for generations, refugees from pogroms and the Holocaust, are being treated as hostile aliens by well-funded secular ideologues and anti-democratic religious zealots. Old prejudices linking Jewishness to corruption, wealth and the exercise of clandestine power are re-surfacing and we need to ask why.

We also need to question why there have been so few public statements of solidarity in response to the Hamas attack. Faced with the horror of Palestinian casualties in Gaza, many non-Jewish progressives have focussed on that, preferring to forget the events of 7th October. Few Jewish people have the luxury of doing so. The cruelty of the Hamas atrocities was live-streamed and publicised by mocking perpetrators. Even for me, a non-Jew, the assaults brought back terrible images of anti-Semitic atrocities of the 1930s and 1940s, many filmed by nazi bureaucrats.

Since October 7th I have expected some form of public statement of solidarity from churches and faith leaders, an expression of grief or horror at what happened that day. All I have heard has been an embarrassed silence. There are prayers for peace and collections for Gaza’s suffering civilians, all of which are worthy and necessary, but in the British context, this is safe territory and not enough.

European anti-semitism started with Christianity. It remains a quietly unacknowledged fault-line within British churches and flourishes unchallenged in Islam’s fundamentalist congregations. Our society needs people to speak out against it, not hide behind collections and prayers, fashionable flags and comfortable slogans.

I have for years supported the Palestinian cause. I know that Palestinians have been subject to racist attacks, prejudice and unjust practices. I deplore the illegal actions of Israeli leaders who have denied justice to a dispossessed people and the often brutal actions of the IDF. However, nothing the Israeli state has done provides justification for the atrocities of that day – any more than those events justify war crimes against Palestinian civilians.

In war, mistakes can happen. Enraged individuals can do terrible things. But, this event was not a mistake, nor did it result from an explosion of rage. It was a military operation, planned well in advance, which targeted civilians and, in particular women and girls, for hideous abuse and humiliation.

Many on the left ask us to offer ‘critical support’ for liberation struggles and urge us to accept that atrocities happen in the process of struggle against oppression. The truth is that nothing good can come from a liberation struggle which tolerates or encourages torture, rape and murder. Such revolutions are rotten at the core and produce bad governments.

I have long opposed Hamas, knowing it threatens human rights, in particular those of women and girls. However, I thought it not as dangerous as other Islamist organisations. I was wrong. The events of 7th October reveal an organisation prepared to deploy the sadistic methods of ISIS, while targeting females and vulnerable others just as brutally as they, Al-Qaeda and the Taliban ever did.

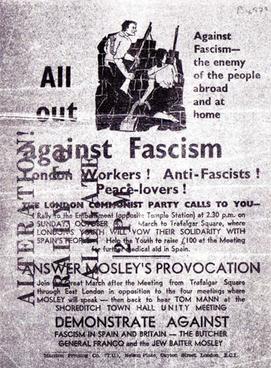

The level of brutality should terrify us, because it is rooted in a form of religious fascism that Britons of left and right, whether secular or of faith, seem peculiarly reluctant to acknowledge. In the past, no one on the left would march alongside fascists. Now, in opposition to Israeli actions, it seems fashionable to do so.

I was struck by the words of journalist Jonathan Freedland who wrote: “…Jews have often functioned as a canary in the coalmine: when a society turns on its Jews, it is usually a sign of wider ill health.”

In our time, anti-semitism is emerging like a virus, a symptom of worse to come. We as a people need to do as we have done before, at Cable Street and beyond, recognise fascism for what it is and stand firm against it: whatever form it takes.